Joshua Gans Optimistic on ChatGPT’s Implications for the Future of Work

Why one of the world's leading economics of AI experts sees the net impact of this new technology as more equalizing, empowering for humans.

Both Joshua Gans and I grew up watching the television series Star Trek: The Next Generation, a show set in the 24th century where at least economically, technology has allowed for greater human welfare. Hunger, material wants, and even the need for money have been eliminated. In contrast, other science fiction shows such as Babylon 5 envision the persistence of today’s economic problems such as poverty, despite immense technological advancement. Even worse, dystopian stories such as The Terminator imagine a future where artificial intelligence (AI) technologies lead to humanity’s displacement or destruction.

A lot has changed in the past three hundred years. People are no longer obsessed with the accumulation of things. We’ve eliminated hunger, want, the need for possessions. We’ve grown out of our infancy.

— Captain Jean-Luc Picard in “The Neutral Zone”

I spoke with Gans to ferret out which type of future is hinted at by the recent release of ChatGPT. Gans is a fellow of the Luohan Academy and a professor of both management and economics at the University of Toronto. He has spent much of his career studying the economic impacts of new technologies. The University of Toronto has become a global mecca for AI studies, exemplified by leading researcher Geoffrey Hinton whose work led to the AlexNet and ImageNet image recognition engines.

As the Chief Economist of the Toronto Creative Destruction Lab, Gans has worked closely with many such AI pioneers. He has written about his insights in books with co-authors Avi Goldfarb and Ajay Argawal including Prediction Machines (2018), The Economics of AI (2019), and Power and Prediction (2022). Gans has also mused on the broader future impact of technology with co-author and Australian MP Andrew Leigh in their book Innovation + Equality: How to Create a Future That is More Star Trek Than Terminator.

1. AI behind ChatGPT moved problems from ‘algorithms’ to general purpose ‘predictions’

In November 2022, the company OpenAI publicly released ChatGPT, a chatbot that uses generative language models. ChatGPT has been lauded as giving very human-like responses to a variety of prompts. In addition to writing text based on user queries, it can also write and edit mathematical formulas and computer code.

Gans explained the realization AI researchers had that led to this: “What if we take all the information on the internet, synthesize it in some manner, combine that with the understanding of language and communication of language that results from it, and come up with what are essentially these large language models?”

The most important transition Gans identifies in his book was the evolution of AI technology from being algorithmic to “prediction” based. Prediction in this context is not Delphic prophecies of the future, but rather ways to predict the best outputs when given certain inputs. This is made possible by training machine learning training with large data sets.

In autonomous driving, for example, early systems were so-called expert systems in controlled domains, programmed by humans to perform based on specific rules: if X, then Y. Training was often through the system’s own trial and error. But with data collection and deep learning now more mature, autonomous driving is being tackled by training from vast quantities of real driving data. Systems learned to recognize patterns across different drives, drivers, and road conditions.

As it so happens, I took an AI computer science course at university. This was just before the revolution in big data and generative AI. We tackled games like chess using mostly algorithmic solutions. We established functions to value board positions and then run algorithms such as minimax, which aimed to maximize the results of my own move while minimizing those of my opponent. Chess can be thought of as an expanding Bayesian tree of possible future moves. But calculating all of this using current computers would take longer than the lifespan of the universe. The American mathematician Claude Shannon estimated the number of moves in chess at approximately 10¹²⁰ and board positions at 10⁴³. So a set of heuristics and pre-built learning, including opening and closing positions, is loaded into most chess programs, along with “pruning” algorithms to avoid evaluating bad branches.

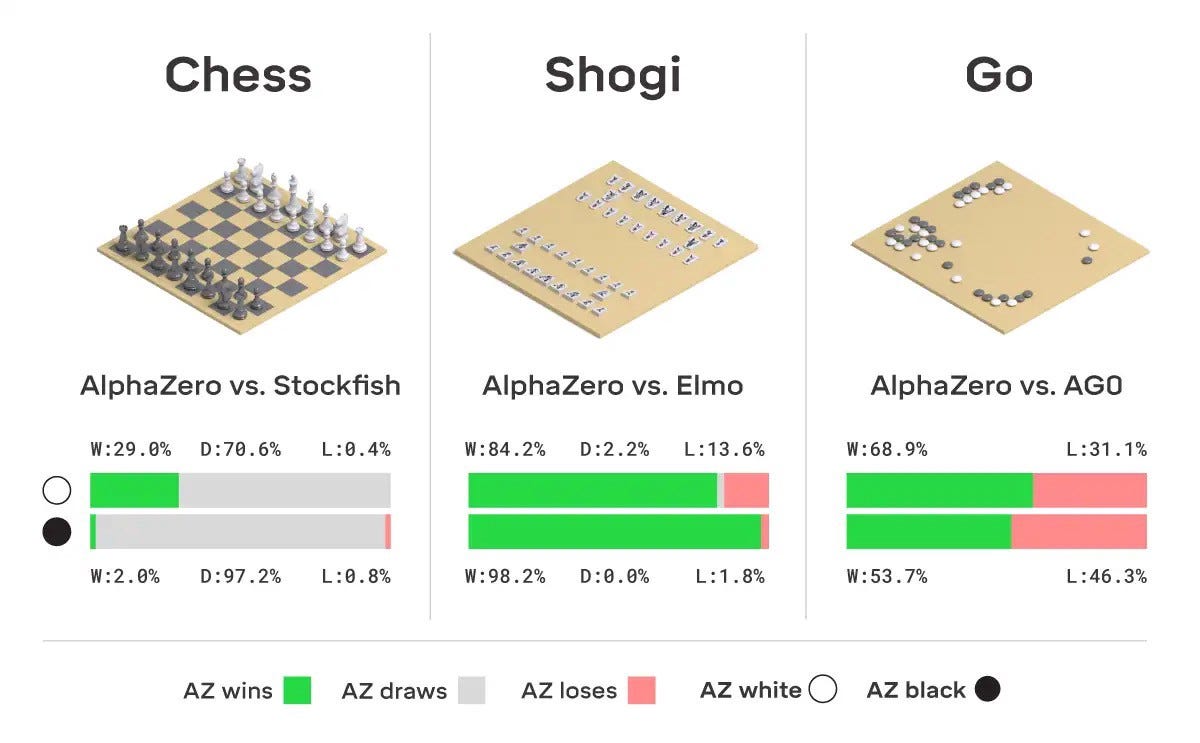

By applying tremendous human intellect and computing power to the game, chess programs such as IBM’s Deep Blue were already regularly beating human grandmasters around the turn of the century. But what was more astonishing to the AI world came later in December 2017, when the DeepMind program AlphaZero beat the reigning chess software Stockfish after only 24 hours of training, without chess-specific domain knowledge. In other words, the program’s creators did not have to be experts in chess. This was an incredible demonstration of how far “prediction” based deep learning solutions had come.

2. Economically, the AI behind ChatGPT allows for better and cheaper machine “predictions”

Language models that drive ChatGPT use similar machine learn powers, trained by AI experts on large data sets to predict what humans want to see. To Gans, the economic crux of what the current generation of AI does is to lower the cost of these predictions. Gans offers an example: “You can put in a prompt such as ‘rewrite the words of the U.S. national anthem in a hip hop style’ or something like that and what the machine is able to do is it predicts what you were hoping that would be, even if you don’t know it yourself.”

The results have caused excitement and anxiety in the media and among researchers. A more powerful version of the underlying language model, GPT-4, is expected to be released sometime in 2023. Many commentators have questioned whether this technology might substitute for humans in the workforce and threaten the livelihoods of white-collar workers. Gans takes a relatively optimistic view for us humans. He draws an analogy: The Internet greatly lowered the cost of communication. Yet, that technology was greeted with far more optimism than alarm. The lowered cost ultimately created abundant new opportunities for workers and new forms of productive economic output.

I pressed Gans on whether ChatGPT technology should trigger the same anxieties that many people share about automation in general. These include fears that the owners of capital will gain relative power, while workers become undermined or unemployed. On the contrary, Gans sees the development of such tools as liberating. Rather than creating mass unemployment, he explains that such technology frees up time for humans to focus on their more high-value capabilities, such as decision-making and thinking. “Everything we’ve talked about now is how you take a person trying to do their job, and they can do it ten times better, or ten times faster, as a result of what these things can do,” Gans says. “Well, that makes people more useful, more valuable, etc. There’s always more stuff for us to do. And this allows us to do it.”

History has analogies that offer some reassurance. Gans points to the digital spreadsheet: “Prior to spreadsheets, people had to do all of those calculations — everything laboriously themselves. The spreadsheet comes in and it boosts their productivity. They’re able to do their current stuff much quicker, and they’re able to do new stuff that they would never have had time for before. I think the same thing is true here.”

3. AI will change the relative values of work and skills

Of course, even if broadly positive, technologies can cause sharp changes in the relative value of skills. For example, experienced London taxi drivers likely found themselves relatively less valued once GPS navigation technologies were introduced. Inexperienced drivers were “upskilled” to navigate London’s maze of streets. Gans takes the “glass half full” view that technology can often be an “equalizer,” in this case for those inexperienced drivers. As another example, Gans points out that ChatGPT technologies can level the playing field for those working in their non-native languages. In particular, this could offer workers in emerging economies a way to upskill their capabilities, potentially reducing geographic inequality.

4. Rethinking human work and purpose

One key question I have been thinking about is what ChatGPT reveals about the nature of our work. I know how ChatGPT broadly works and understand most of its limits. And yet, I also can’t help but feel anxious about these technologies displacing what we humans do. I ran past Gans my worry: “what if a lot of what we do isn’t actually that intelligent? For instance, what if most writing is a relatively rote process in which we need to reproduce something very similar to what we’ve written before?” For every Ernest Hemingway, there are at least 99 of us who scribe more pedestrian text based on some set pattern.

“I think that’s an excellent way of putting it,” responded Gans. “I think people have underestimated how much of what they do on a day-to-day basis is almost ‘routine’.” As programs like ChatGPT displace more routine writing, humans will need to maintain a comparative advantage in other skills. For example, he notes that the need to ask questions and know AI’s constraints will be a crucial new skill set. “ChatGPT, like the spreadsheet, equalizes everybody’s ability to answer [certain] questions. On the other hand, that increases the demand or worthwhile bonus of asking questions. And so effectively, we’ll do that,” explains Gans. “People have to ask those questions. Machines aren’t asking any questions. And, interestingly enough, asking the question is something that’s taken a lot of human cognition.”

One of the fields feeling immediate pressure from ChatGPT has been teaching. As an educator himself, Gans proffers his view: “What it exposes is, if it was possible for ChatGPT to pass your exam, then you weren’t teaching something that was useful, and you weren’t assessing on something that’s useful enough… and so it forces you to start thinking about what should I really be creating as an assessment.”

Gans says that if he wants to assess what students can do without ChatGPT, he will put them in a room without the Internet and have them take a test. However, Gans elaborates, “if I want to test students’ ability to apply this knowledge outside of the classroom in the future, I want them to have ChatGPT. I want them to use it so that I can assess their ability on stuff that isn’t that. It’s both a wake-up call and also a natural evolution of how we do things.”

5. Even if the future is not dystopian for humans, adjustments can be complex

Luohan Academy has interfaced with some of the world’s leading thinkers on how technology affects work and labor markets. David Autor’s work on job market evolution, presented at Luohan last year, is often-cited research that chronicles the evolution of the job market. He shows clearly that work does not stay static and new types of work develop in response to technological and social change. Autor et al (2021) estimated that over 60% of job categories in 2018 did not exist in 1940. There are many more data scientists and yoga instructors now than just 20 years ago.

In general, economists have pointed to history to disprove the “lump-of-labor fallacy,” the view that there is only a fixed amount of work to be done. We all have a long queue of things we would do if we had more time. I asked Gans if he is optimistic that technology such as ChatGPT will lead to a reallocation of work rather than a mass displacement of workers. “I am, because I think we’ve seen very big technological revolutions before and we haven’t seen massive, long-term unemployment, says Gans. “There’s nothing I can see here that suggests it’s going to be fundamentally different. These aren’t really thinking machines, these are predicting machines, okay? I guess I’m in the school of people who believe that we ourselves are more than prediction machines.”

Perhaps this optimism at the macroeconomic level about the far future should be couched. We have to get there first, through many micro adjustments. Anton Korinek of the Brookings Institute presented to Luohan in November 2022 his more worrying research on the potential of AI-enabled automation to displace much more of the workforce than the benign scenario offered by Gans. This was based on his paper “Preparing for the (non-existant?) future of work” (Korinek, 2022). According to Korinek, jobs may not go away, since labor supply is relatively inelastic, but the rising relative value of machines vs. workers is a cause for worry. Unsurmountable inequality can destroy the social fabric.

The messy reality is that adjustments are not costless to everyone. And in a complex global economy, change is not simple to predict. The first industrial revolution led to serious questions of man’s worth and potential alienation. Now that we white-collar workers are feeling anxiety about what we have excelled at, it’s hard to imagine there will be scant impact. Society should be more aware of these changes and scholars like Gans and other Luohan community members are playing a critical role in helping us understand them.

Upcoming Book Talk: On Feb 8th, Luohan Academy will be talking with Avi Goldfarb, a frequent collaborator of Joshua Gans. We will be discussing Goldfarb’s recent book, Power and Prediction, co-authored with Gans and Ajay Agrawal.