Joel Waldfogel: How technology is enabling a 'digital renaissance' for creative content

The scholar of creative industries on why digital technologies have been net positive for content creation, big gains from 'random long tail' blockbusters, and the crucial role platforms play

Professor Joel Waldfogel is one of the world’s leading experts in the economics of the creative and media industry. He is the Frederick R. Kappel Chair in Applied Economics, Strategic Management & Entrepreneurship at the Carlson School of Management. He was previously the Chair in Business and Public Policy at Wharton. He is the author of several books, most recently Digital Renaissance in 2018.

A social planner’s goals for the creative industry

As someone trained in traditional economics, Professor Joel Waldfogel became interested in content businesses because of their interesting economics - including their high fixed costs, technologically determined distribution, and large degree of intangible intellectual property. He began by studying the “traditional” ratio station market with collaborator Steven Berry. In the 1990s, digital technology began disrupting these industries. In music, Napster was launched as the first large-scale peer-to-peer file sharing services. Other disruptions, including Youtube and Internet radio followed. From 1999 to 2020, the U.S. music industry saw a 70% drop in revenue. Digital monetization channels were still not well-established, and pirated or free content was available.

Waldfogel studied the industry during the digital technological disruption. He published a number of papers on this subject such as Piracy on the High C’s: Music Downloading, Sales Displacement, and Social Welfare in a Sample of College Students (2004), Music file sharing and sales displacement in the iTunes era (2010), and Music piracy and its effects on demand, supply, and welfare (2012).123 One of his key findings in research was that Napster and related technologies that aided piracy were displacing somewhere around 1/6 to 1/3 of legitimate sales.

Despite his findings that piracy and disruption harmed many in the music industry, Waldfogel is unsure the results ended up being negative for society. Instead, he thinks technology led to a ‘digital renaissance’ in creative content that saw a flourishing of content creation. This view is the subject of his research and a book “Digital Renaissance” published in 2018.

The dawn of the digital renaissance

What is society’s measure of success in the creative industries? Waldfogel grounds his views in the goal of the promotion of the creation of creative content. He prioritizes the question: are we seeing more quantity and quality of creative output?

Historically, technology was deterministic in the market for creative content. Due to limits in screens, a movie could only be viable if it had a hundred or more people in every theater per night. Similarly, physical media such as books, albums, and DVDs needed enough buyers in each physical store. Digital technologies now make the cost of distribution very low and remove geographic constraints: a movie can potentially be viable if 50,000 people globally watch it.

At the same time, an important factor often undervalued by economists but appreciated by creators has been that production has gotten easier and cheaper. This has been particularly in music and videos. For example, GarageBand has enabled musicians and podcasters to create professional content easily.

“It has traditionally cost a lot of money to bring a new music album to market or a new movie to market. And so if all that happened, was the undermining of revenue through piracy, one should rationally expect… business and consumers will be left high and dry with nothing to watch and listen to. What came to the rescue was that technology not only enabled stealing, technology also enabled much, much lower cost of production, distribution and even promotion.”

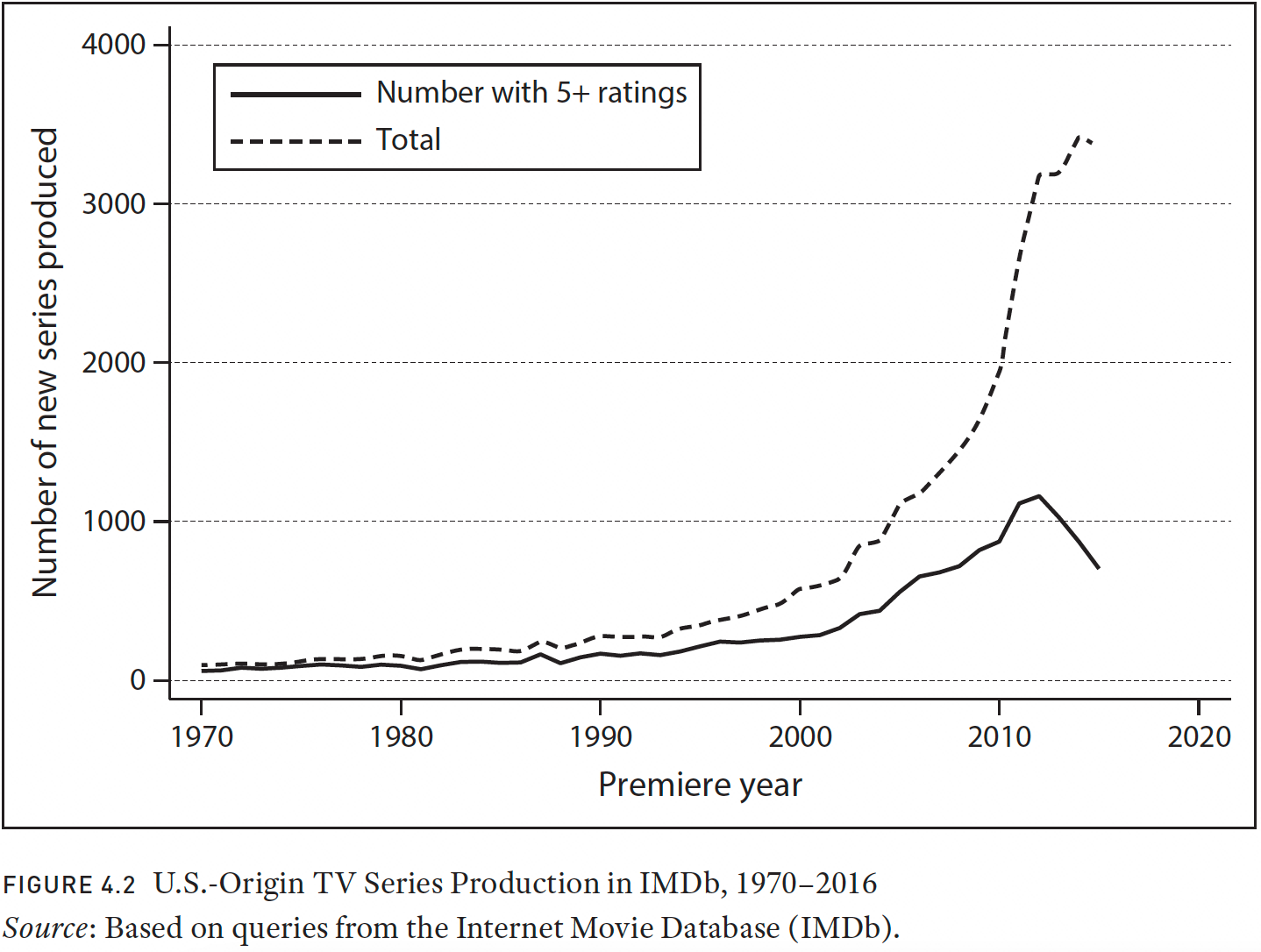

So what has been the impact of both lowered cost of creation and of distribution? Waldfogel’s book Digital Renaissance covers his decades of research answering this question.4 What it shows is a marked increase in content and no decline in quality content being produced, which many feared. To measure quality, Waldfogel meticulously combs historical rankings by consumer ratings and by professional critics. For example, he uses Billboard or Rollings Stones ranking for music, IMDB and critics' reviews for movies, and bestseller lists for books. All of these measures seem to show no discernible decline in quality over time.

Will we have even more content with the ongoing advances in generative AI? ChatGPT, Bard, Tongyi Qianwen, Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, Dall-E are all examples of tools that augment humans in creating works. It seems likely we will again see more quantity. What will be the impact on creators and consumers? To Waldfogel, is an open question. There is already a great deal of content already. He is curious to see whether AI creates content that is similar or derivative to what already exists or helps people really create unique and novel works.

Chart from Digital Renaissance (2018) showing increases in TV series along with ratings:

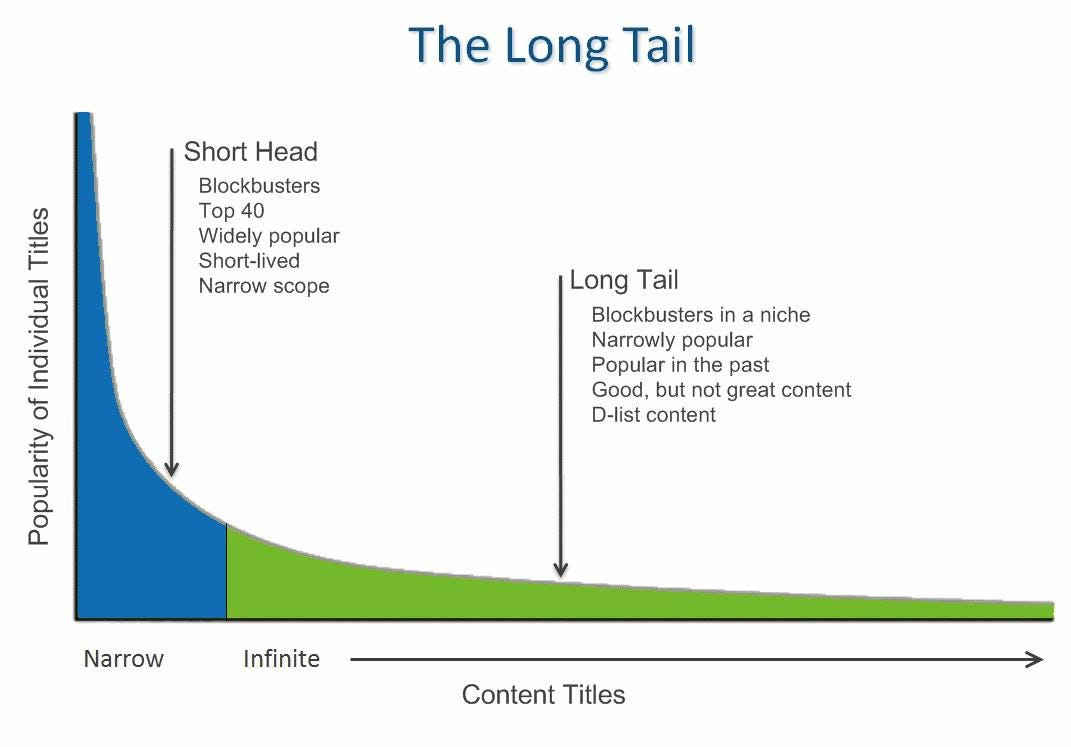

The immense power of longer tails and right-tail winners

Many economists think there are welfare gains from variety, and there is positive value in the so-called "long tail" of goods. Indeed, there has been research measuring this. In industrial organizations (IO) research, a large body of literature has attempted to quantify gains from variety, usually for goods. In the digital era, Luohan fellow and Stanford professor Erik Brynjolfsson was responsible for a seminal 2003 paper. Back then, Amazon had 57 more titles than a typical bookstore. The gap is likely much greater today. found significant gains from product variety with growing availability of books on Amazon.com.

More recently, research by Brynjolfsson and Luohan Academy scholars Xijie Gao and Long Chen was published in a working paper Gains from Product Variety: Evidence from a Large Digital Platform (2022), which shows the value of variety on platforms is 40x greater than any price advantages offered.5

"If you were to say triple the number of new products, then how many products that wouldn't otherwise have existed, but for the cost reduction end up being valuable? In a study I did with Luis Aguilar, we looked at this “random long tail” in music and found that it's around 20 times bigger than the traditional long tail."6

Waldfogel believes the power of the long tail is particularly strong in content goods. This is due to two factors. First is the intrinsic “traditional long tail” of just having more products available that make it easier to fit specific needs better. But Waldfogel points out there may be much more societal welfare gains from the “random long tail” of the unexpected blockbusters, what he calls right-tail winners. In the past, due to distribution bottlenecks and production costs, less of this content would have been produced in the past. Society has always had its share of shoestring-budget films and garage bands that struggled in the face of rejection by gatekeepers and ultimately made it big. But many more did not get produced because they were never rejected. The digital renaissance now makes these products far more likely and Waldfogel believes these have a large impact. He points out that some 10% of bestseller books are now self-published, and some 20% of music streamed is independently produced.

To Waldfogel, the economic mechanism behind the value of the random long tail “is that the traditional gatekeepers are not able to predict consistently what will become popular. They often do not take on content that actually ends up being popular. In the digital era, much more content is created and published that is not going through traditional gatekeepers. While much of this is not viable, some of it becomes highly successful, which led to the phrase Waldfogel often quotes “nobody knows anything” coined by Hollywood writer William Goldman.

Excerpt from Waldfogel’s paper The Random Long Tail and the Golden Age of Television:

Yet, the appeal of new products—especially cultural products—is famously unpredictable. William Goldman (1989), author of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Princess Bride, and many other screenplays, has written that “nobody knows anything” about which potential Hollywood products will find favor with consumers. This idea—the unpredictability of new product appeal—is borne out in more systematic research on books, movies, and music. It is difficult to know prior to undertaking the investment whether a project will find favor with consumers (Caves 2000).

The platform’s crucial role in the digital renaissance

Large digital platforms play important roles in all of what was discussed above, and thus have been crucial players in ushering in the digital renaissance. Primarily, they have helped in distribution and discovery. They are matchmakers that gather content, distribute it, and get it in front of people in very effective ways.

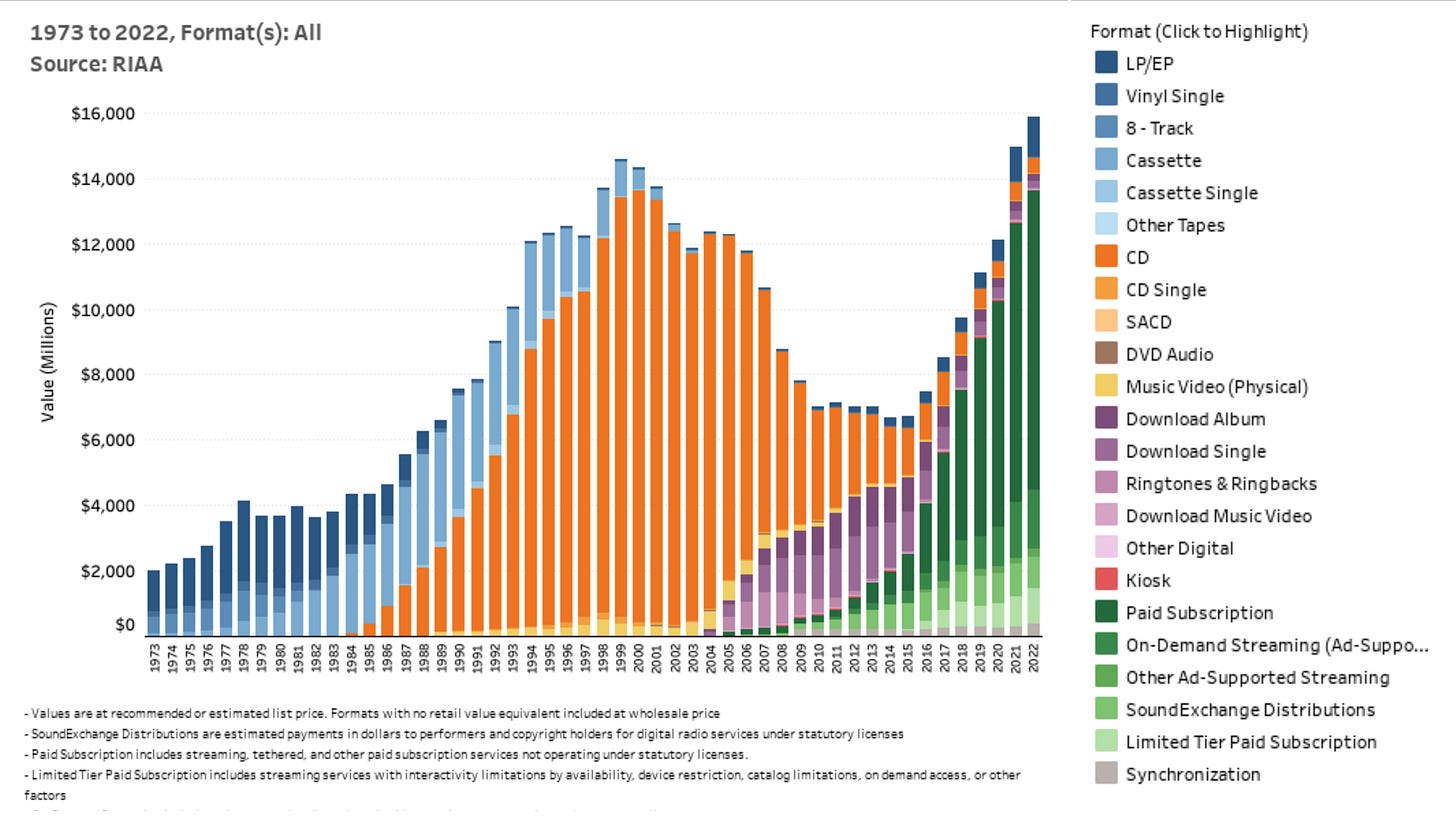

The new business models and in particular, the pricing model, of streaming has also had an immense impact. For one thing, it has finally made up for the drop in revenue in the media industries. In music, we have seen a sharp rise in revenues from the nadir in the mid-2010s to surpassing the previous peak. Beyond supporting rights holders and creators, the pricing models have another important feature to support the digital renaissance. “All you can eat” pricing for streaming lowers the opportunity cost of trying something new.

In fact, platforms can play major roles in promoting more variety of content through their steering ability. In current research Waldfogel and Aguilar try to show that Spotify purposely includes more independent music in its curated playlists that many users like to stream. For users, this introduces them to a wider variety of music that they may like. For Spotify, it reduces their royalty payments as independent music costs less than popular music from the major labels. Waldfogel discusses this research in the Luohan Webinar Countervailing Platform Power: Spotify and the Major Record Labels, 2017-2020.

U.S. Recorded Music Revenue by Format, 1973 - 2022

What does Waldfogel think of the role played by platforms? On the face of it, the current market dynamics might be worrying. Back in the 1990s, Walmart raised issues by having 10% of the retail content market. This seems quaint by today’s standards. Now just two players, Spotify and iTunes, account for at least 2/3 of the U.S. music streaming market. The obvious fear it that powerful platforms may become a “bottleneck through which all upstream products need to pass.” Yet Waldfogel is not clear there is this type of abuse, and he is not obviously worried at this point.

It’s possible that the platforms potentially have the same incentives as consumers - help consumers discover new content and thus promote more content. This is not inconsistent with them using various ways to increase their own bargaining power with their suppliers. Some platforms have units that compete with these suppliers. In books, Amazon launched Amazing Publishing and Kindle Direct Publishing. Both are upstream channels that compete with or bypass the traditional publishers that are responsible for most of Amazon’s book sales.

“At Spotify, the 50 million songs include a ton of songs that don't come from the major record labels or even the big indies. I think the platforms are figuring out ways for consumers to discover this stuff and so one could consider pushing this non traditional stuff as a mechanism for the digital renaissance for which would make it good, or one could think about it as the platform strong arming their suppliers.”

Whether or not this is good or bad is something Waldfogel thinks society needs to study and think carefully about. One question is whether platforms end up adopting the roles of the traditional gatekeepers of the past. Right now that doesn’t seem to be happening. But more research and information is needed. Society is discussing the role and power of digital firms but as Waldfogel puts it: “there's less evidence than then then there is rhetoric in many of these conversations.”

In these critical questions, Professor Waldfogel and his colleagues are contributing meaningfully to understanding this industry, its digitalization, and the fast changing business models that are all helping to bring about the digital renaissance.

Rob, Rafael, and Waldfogel, Joel. 2006. “Piracy on the High C’s: Music Downloading, Sales Displacement, and Social Welfare in a Sample of College Students.” Journal of Law and Economics 49, no. 1:29–62.

Waldfogel, J. (2012). Music piracy and its effects on demand, supply, and welfare. Innovation Policy and the Economy, 12(1), 91-110. https://doi.org/10.1086/663157

Waldfogel, J. (2010). Music file sharing and sales displacement in the iTunes era, Information Economics and Policy, Volume 22, Issue 4, 2010, Pages 306-314, ISSN 0167-6245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoecopol.2010.02.002.

Joel Waldfogel, Digital Renaissance: What Data and Economics Tell Us about the Future of Popular Culture, Princeton and Woodstock, Princeton University Press, 2018

Brynjolfsson, Erik and Chen, Long and Gao, Xijie, Gains from Product Variety: Evidence from a Large Digital Platform (December 2022). NBER Working Paper No. w30802, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4312049

Luis Aguiar & Joel Waldfogel, 2018. "Quality Predictability and the Welfare Benefits from New Products: Evidence from the Digitization of Recorded Music," Journal of Political Economy, vol 126(2), pages 492-524.