Luigi Zingales: SVB reveals regulatory failings in the age of social media bank runs

Zingales on the many failures at regulators that led to SVB collapse, the folly of relying on financial repression to save banks in the information age, and his hope for CBDCs

Luigi Zingales is the Robert C. McCormack Distinguished Service Professor of Entrepreneurship and Finance at the University of Chicago and the Director of the Stigler Center. He is the author of 2 popular books on the political economy: Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists (2003) and A Capitalism for the People (2012). He is perhaps best known as the co-host of the leading economics podcast Capitalisn’t.

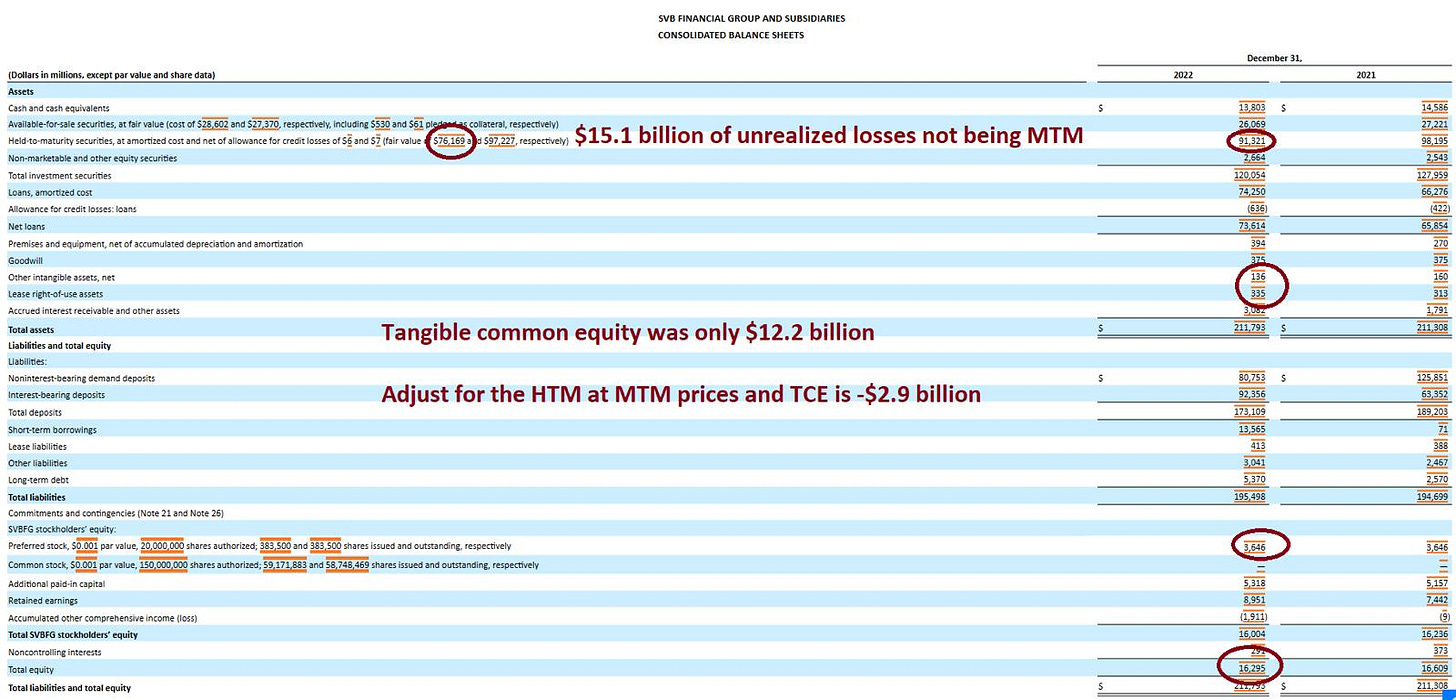

In a recent episode of Capitalisn’t following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Luigi Zingales interviewed 2022 Nobel laureate and University of Chicago colleague Douglas Diamond. The Diamond-Dybvig model is a key conceptual framework for understanding bank runs, particularly how sound banks can fail due to a self-fulfilling prophecy.1 Diamond explained why SVB was not a typical liquidity-induced run, as immortalized in the film It’s a Wonderful Life (1946). Instead, the bank was financially insolvent. SVB had assets whose values, even if sold at market prices, did not cover its liabilities. This problem cannot be ultimately solved by a liquidity window from a lender of last resorts.

Zingales sees failure at all levels. Although management failure was front and center in SVB’s collapse, Zingales sounds less concerned about this idiosyncratic issue at one bank. Instead, he worries more about the systematic failure of regulators to take action towards an obvious problem across the wider banking sector. Public FDIC data alone showed a $620 billion mark-to-market loss in the assets of US banks at the end of 2022, out of total equity of just over $2 trillion. Four academics recently published a paper that estimated an even higher capital hole of over $2 trillion.2 Zingales is upset at how this problem led to no early actions by regulators.

Can we rely on financial repression?

So what are regulators thinking? After the interview with Diamond, Zingales spoke to Eric S. Rosengren, the former president of the Boston Fed. Rosengren noted that although some banks were currently insolvent, time could be a solution. One view was that the banking system could do fine if only given sufficient time for those securities to expire closer to or at maturity. So short-term liquidity windows would tide over the problem for lenders until they reached the promised land.

So I have to bet that my depositors don't notice, they stick around for 20 years of mistreatment, and if they stick around for this 20 years of mistreatment, I am not in default.

To Zingales, Rosengren’s long tenure at the Fed means he is good representation of the views of the regulatory community. But this view bothers Zingales, because it presumes that depositors would always stay. Zingales states, “all this argument is based on the idea that depositors are sticky, or my less polite way to say it, dumb.” The regulators are presuming a certain level of what economists call financial repression. But can we assume such a level will maintain going forward?

Semper Fi or Semper Infidelis?

Zingales believes the answer is no, and SVB shows the dangers of assuming depositors are lazy. He points out there were actually two ‘runs’ that led to SVB’s rapid collapse. The world paid most of its attention to the latter run that immediately preceded the bank’s March 10 collapse. But that run was triggered by an announcement that SVB was earlier forced to sell $21 billion of securities to meet growing withdrawal requests. This was around 10% of SVB’s total deposits. To Zingales, this is Exhibit A in showing that depositors cannot be assumed to be sticky. These early movers may have included the more astute customers, with either early warnings about SVB’s solvency or hunting for better yields, Combined with the effects of a tech fundraising downturn, the withdrawals and losses caused to SVB triggered a more rapid and larger run. By then, the bank was already doomed.

What made this run particularly accelerated were chat groups and social media. According to California’s bank regulators, $42 billion of deposits were requested in one day alone from a bank with $175.4 billion at that time. SVB’s highly concentrated client base spread the word on Twitter, Slack, and other social channels.

I asked Zingales if he is worried about a slower motion but more widespread series of runs happening across the banking sector. News reports abound of businesses and individuals moving from smaller to bigger banks. He is worried, and like me, he was struck by something Janet Yellen said that would only serve to encourage this.

In Big We Trust?

In a little hilltop village, they gambled for my clothes

I bargained for salvation and she gave me a lethal dose

I offered up my innocence I got repaid with scorn

Come in, she said

I'll give ya shelter from the storm- Bob Dylan (Shelter from the Storm)

If I were a corporate treasurer already looking at moving my money from a smaller bank to one of the large mega-banks, that calculus got starker after a tense exchange in Congress. Over the hectic weekend when SVB and Signature Banks failed, the authorities announced aggressive actions to try to stem a larger banking crisis. They covered all depositors, including all uninsured amounts, at SVB and Signature Bank by classifying them systemic dangers. They also created a lending and liquidity facility at the Fed that lent out against securities at par value, effectively giving banks a liquidity bridge that ensured none would go bust due to holding ‘safe’ securities that had fallen in price. However, despite these strong tools that make another collapse unlikely, what they did not explicitly do was to commit to guaranteeing all deposits going forward.

At a session of the Senate Finance Committee on March 16, Senator Lankford of Oklahoma asked Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen whether she could commit to guaranteeing all depositors at the small community banks in his state in the same treatment given retroactively to the depositors at SVB and Signature. To which Yellen took pains to say that a bank’s depositors only gets that benefit if “a majority of the FDIC board, a supermajority of the Fed board, and I in consultation with the president, determine that the failure to protect uninsured depositors would create systemic risk and significant economic and financial consequences.”

I asked Zingales about Yellen’s answer and he did not hold back: “I cannot believe that Janet Yellen did that.” He understood there may not be explicit authority to back all deposits in the US banking system but given their ability to define systemic risk exceptions, “if she didn't have to have the authority, she had to create that authority ASAP.” He suspects they will eventually need to give stronger guarantees. Otherwise, we will only see more outflows from smaller banks to “systematically important” ones - i.e., more concentration at the top. Zingales was also bothered by the arbitrariness which gave a lot of discretion to regulators.

She [Yellen] basically said, I am in charge of deciding who survives and who doesn't. And by the way, if you like me and you're kind to me then you're more likely to survive. This is unbelievable.

Banking faces the era of social media?

Technology is disruptive to many industries. In fact, it’s amazing to think that banks in the US have not faced very much disruption to their usual humdrum business despite the rapid changes in other facets of consumer life. This may be owed to the entrenched nature of the banking business model and status quo-biased regulations.

But the combination of digital technology and disruption from a macro shift to rising rates may be adding pressure to the traditional banking model. “We live in a social media world where the response time is in a matter of minutes, not even days.“ While this is new, Zingales rejects a convenient narrative that this is not something the authorities like the Fed could have reasonably expected. He does not want to give the Fed a pass for the situation that developed over time. In fact, Zingales believes this problem is big enough and the potential consequences grave enough that there should be an independent investigation of the regulators modeled after the presidential commission set up to investigate the 1986 Challenger disaster. He published an op-ed advocating for this shortly after our talk.

I think that it was a mistake for the Fed and the government not to announce an insurance policy above the threshold for transaction deposits. And I think they would be forced to do it. And it's better sooner than later.

In the short run, Zingales believes it’s important to stop the runs. Authorities should guarantee all low or no-interest transaction accounts as was done during the 2008-9 financial crisis. Because what SVB showed is that even small banks can be systematic when everyone is connected. Zingales’ wife, who is seldom involved in finances, asked him about their bank accounts after hearing news reports in social media.

In the long run, what are possible solutions? Technology may have a role. Zingales’ idea is for central bank digital currencies for all transaction accounts, to avoid the risks with a fractional reserve banking system. In his ideal world, banks would not take demand deposits but instead would take time deposits of different durations thus cutting down on the risk of bank runs. You cannot, after all, run the central bank of a fiat reserve currency.

Some may criticize Zingales’ proposal as unrealistic given interest groups, or ignore potential disadvantages to this kind of system. But the idea of central bank digital currencies has traction among many scholars. Luohan friends like Darrell Duffie and Richard Holden have also advocated for CBDCs. Whatever happens, at Luohan Academy we look forward to hearing more insights from these reputed scholars.

Diamond, Douglas W & Dybvig, Philip H, 1983. "Bank Runs, Deposit Insurance, and Liquidity," Journal of Political Economy, University of Chicago Press, vol. 91(3), pages 401-419, June.

Jiang, Erica Xuewei and Matvos, Gregor and Piskorski, Tomasz and Seru, Amit, Monetary Tightening and U.S. Bank Fragility in 2023: Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs? (March 13, 2023). Available at SSRN: