Wolfgang Lutz: Demographic slowdown does not spell doom

The renowned demographer dispels gloomy population news out of China, sees gains from technology, but believes action is needed to ensure everyone shares in the benefits.

Wolfgang Lutz is one of the world's leading experts in the field of global population development and the interactions between demographic changes, society, the economy and the environment. Lutz is the Founding Director of the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital. He is Deputy Director for Science at IIASA and holds a professorship at the University of Vienna. He has published over 280 scientific articles, including 24 in Science, Nature and PNAS.

In January, news was abuzz that the world’s currently most populous nation - China - saw a population decline for the first time in its official census. This was earlier than forecast and led to a number of headlines. “The Chinese century is already over” declared the Japan Times. “China’s Population Falls, Heralding a Demographic Crisis” appeared in the New York Times. “China’s first population fall since 1961 creates ‘bleaker’ outlook” was the Guardian’s take.

If these headlines represented the prevailing views among global news outlets, Professor Wolfgang Lutz apparently did not receive the gloom and doom memo. It’s not that he doesn’t see the problem of declining population. He is after all one of the world’s foremost demographers and has extensively studied how population dynamics affects societies. A count in 2021 showed he published over 270 scientific articles, with 13 of them in Science and Nature. He founded and leads the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital in Vienna which is a joint project of the University of Vienna, the Austrian Academy of Sciences, and IIASA. He is also Deputy Director for Science at IIASA.

We are now probably seeing the end of world population growth in the second half of the century, where we will reach a peak more or less 10 billion people.

Lutz believes world population will peak sometime this century, then decline. But he does not believe this will be negative for our social and economic well-being.

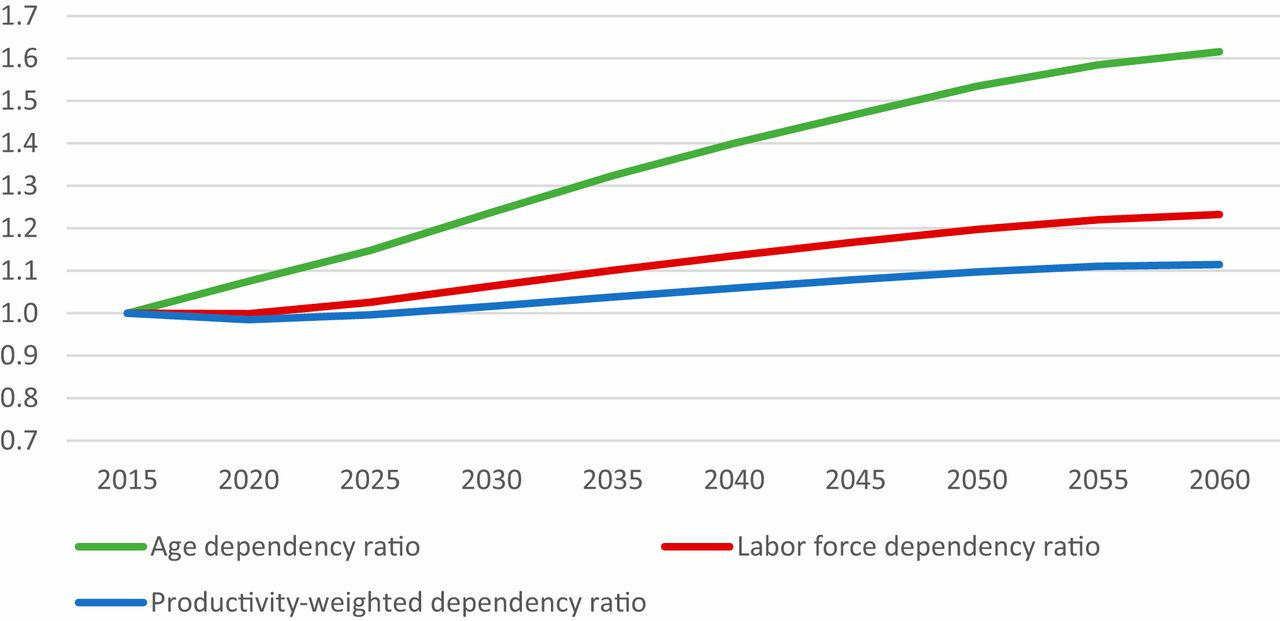

During an earlier talk in a Luohan Academy Frontier Dialogue symposium on the aging world, Lutz discussed his research on the changing structures of populations. Most superficial news reports cover mostly the headline number of population age structure. This is usually represented as the “age dependency ratio” (ADR) which tries to represent how many people need to be supported by every worker, with age 16 to 64 usually defined as working age. But assuming that work corresponds solely to a certain age bracket misses dramatic change in society.

Another year older, another year wiser?

Lutz thinks Singapore shows clearly how large the changes within the population can be. Singapore is an economically advanced city-state that holds clues for developing nations. During his talk at Luohan, Lutz showed the following charts for Singapore 50 years apart. During this period, Singapore has gotten older even as its population more than doubled. But looking at the dark blue area, it has gotten dramatically more educated. This change is particularly acute among women, who have closed the gap with men in educational levels. Women have also entered the labor force.

When we account for the increases in both labor force participation and education, the increase in dependency does not look so stark, and rises only modestly in the decades to come.

No Crisis for Old Men?

Let's return to the question, whither China? On this, Lutz has researched the problem. He penned a paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States (PNAS) with scholars Guillaume Maroisa and Stuart Gietel-Bastenc that covered his views on China’s titled “China's low fertility may not hinder future prosperity.”1 On the pessimism about China when discussing the population, the authors wrote: "These prognostications are partly based on a simplistic and misleading concept of age dependency that assumes that everybody above age 65 is an economic burden and every adult below this age is an (equally) productive asset."

One of the key conclusions of the paper was that productivity-weighted labor force dependency ratio (PWLFDR) forecast a more benign scenario for China's future. The PWLFDR, introduced by two of the authors in Marois et al. divides the number of inactives (the population out the labor force irrespectively of their age) by the number of people in the labor force, weighted by a productivity factor associated to their educational attainment.2

Because China has invested so much in the education of young people, better and better educated people will move into the working ages. And therefore, overall productivity is likely to increase and economic growth can continue.

Children in the (work-life) balance

We turned to the topic of fertility and what society can do to encourage it. According to Lutz, demographers have been surprised by how low fertility has dropped in countries like Korea, where it now stands at 0.7. If not raised, he population will halve this century. The government is well aware of the problem, but its knee-jerk policy responses may be making things worse. Lutz is particularly frustrated a Korean prime minister advocated working longer and harder to account for declining population.

But what Lutz has learned in his studies across societies is that the core problem of family formation is the need to balance work with family life. “People want to have a fulfilled life, which includes a professional career… but it also includes satisfactory private life, including family and children. And you need to have time for this.”

Europe provides insights, since it encompasses a range of countries to compare. To Lutz, it is no surprise that the Scandinavian countries have both some of the highest female labor force participation rates, and some of the highest fertility rates. Family friendly policies at workplaces are a key feature, for example not scheduling meetings late in the afternoon when some parents need to pick up their children from school. Societies that prioritize this will ultimately see higher birth rates and higher growth rates.

If you go to a Swedish company, there is no meeting scheduled after 3pm because then both men and women go home, pick up the children and spend time with their family. And this turns out to be both productive for the economy, as well as leading to higher birth rates.

Technological progress to the rescue?

The recent advances in artificial intelligence, particularly generative AIs such ChatGPT, has been much discussed and inspired both cornucopian and dystopian scenarios. Leaving the existential and ethical challenges aside, there seems to be a general consensus among economists such as in the Luohan community that the current advances in AI should boost productivity.

I asked Lutz his views. To Lutz, the rise of these potentially revolutionary technologies only goes to demonstrate his view that society can continue to be productive despite slower or negative population growth. But Lutz believes we cannot just passively take the development of these technologies if we want to convert these potential productivity benefits to broader social welfare. Lutz is confident these technologies will not displace the need for humans. Even if they really do replace a lot of what humans do today, he thinks we will always need to do things for meaning in our lives. Caregiving for others, looking about our community and environment, are types of work that will always be meaningful. But Lutz believes society will need to focus on two areas for productive technology to be broadly beneficial. First, we must ensure people are sufficiently educated to be able to leverage the new technologies, to gain “higher and higher skills in order to cope and control these computers.” Second, Lutz believes society must carefully ensure economic equity is maintained with the new wealth created. If both of these potential “threats” can be managed well, Lutz sees society being able to channel the new productivity into what he calls the “well-being industry” which would increase general social welfare.

In general, Lutz is more optimistic than pessimistic about our future. This positive inclination derives not only from his belief in the future potential of human ingenuity, but from his deep study of where we came from in the past. While we fret over an aging population, we should keep in mind this situation has arisen from the world’s population becoming educated, wealthier, economically secure, and living longer and healthier into old age. In particular, women have become much more educated, found rewarding careers, and are now better able to choose the timing and size of the family they want.

G. Marois, S. Gietel-Basten, W. Lutz, China’s low fertility may not hinder future prospects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2108900118 (2021).

G. Marois, A. Bélanger, W. Lutz, Population aging, migration, and productivity in Europe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 7690–7695 (2020).