Erica Jiang: Timely research shows how bank-level data can reveal US banking system fragility

The USC Marshall professor co-authored a paper immediately after SVB's collapse using detailed bank-level data to give a precise estimate of risks to the US banking system

Professor Erica Jiang is Assistant Professor of Finance and Business Economics at the USC Marshall School of Business. She is a scholar of the financial sector, particularly in banking, shadow banking, and household credit.

On March 13, 2023, just three days after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Professor Erica Jiang and three co-authors published a paper showing in exquisite detail just how vulnerable the US banking system was to the risks that doomed SVB: Monetary Tightening and U.S. Bank Fragility in 2023: Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs?1 Estimating the mark-to-market asset values at US banks to be $2 trillion less than reported values, the paper attracted intense attention. It has been cited in the Economist, FT, Bloomberg, Washington Post, and so on.

Jiang sat down to discuss the paper in a Luohan DiTalks. The research was a natural extension of pre-pandemic research conducted with her co-authors Matvos, Piskorski, and Seru that aimed to give a deeper understanding of the funding structure of the US shadow banking sector compared with the formal banking sector. A working paper was published in March 2020 titled Banking without Deposits: Evidence from Shadow Bank Call Reports. For this research, the team meticulously collected data from thousands of quarterly “call reports” that financial institutions file with their regulators. These offered detailed breakdowns of their assets and liabilities. This data and experience would be crucial to the latest research.

As the collapse of SVB was happening in the background on Friday, March 10th, the team held a call to discuss an update to their original research to shed light on the current crisis. They felt the previous research gave them the foundation to dive into the assets and liability changes in the banking sector. They worked through the weekend to update data for over 4800 banks, then analyzed the data. Incredibly, the paper was released just three days later on March 13th to wide public interest.

Assets deteriorated during unprecedented pace of rate increases

The first step was to gauge changes in asset prices from 2022 Q1 and 2023 Q1. Assets covered included loans and traded securities, such as MBS, CMBS, ABS, and Treasuries and together comprised 72% of the $24 trillion in US bank assets. The team used the leading benchmarks as proxies to estimate prices.

Changes in proxy indices (2022Q1 to 2023Q1):

Fed Funds Rate: 0.08% → 4.57%

SPDR Portfolio Mortgage-Backed Bond ETF-SPMB: -11%

iShares CMBS ETF: -10%

10-20 year Treasuries: -25% (iShares ETF pricing)

30-year Treasuries: -30% (iShares ETF pricing)

Interest rates rose from a long period of low rates, causing bank assets to decline in value:

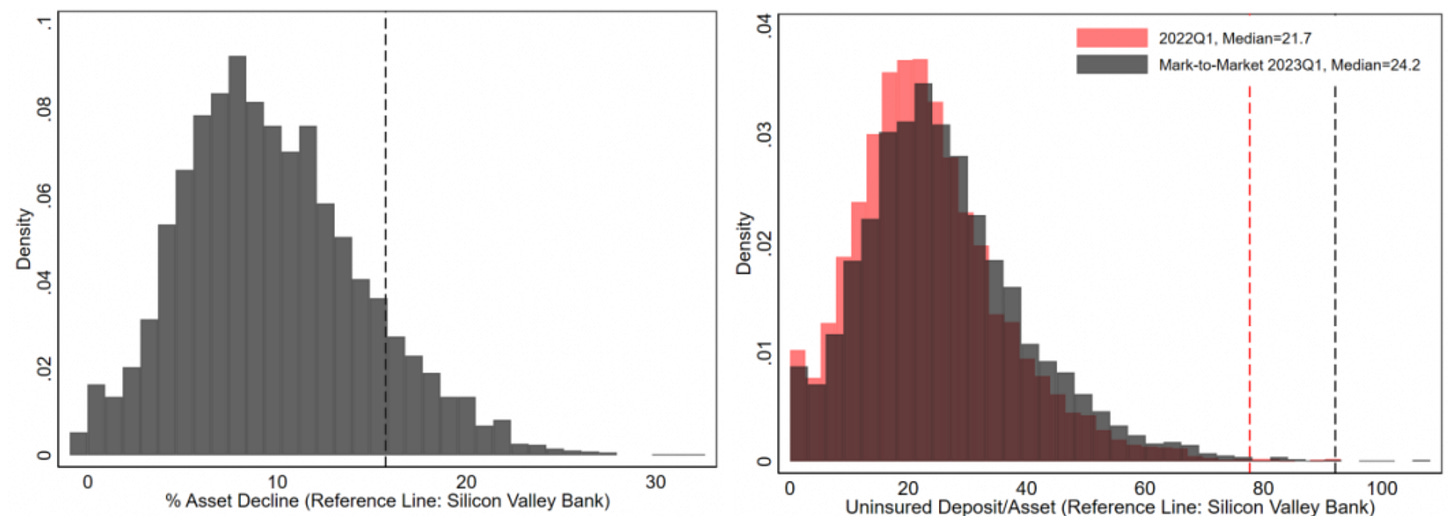

Plugging the numbers in, the team found an average decline of 10% in asset prices, with the bottom 5th percentile of banks experiencing a decline of around 20%. This meant total US banking system assets are ~$2 trillion less than currently reported. This is similar in scale to total equity in the US banking system and markedly more than the $620 billion estimate announced by the FDIC for a limited set of assets.2

Some explanation for why SVB got into this situation was discussed in a prior Luohan DiTalks: How being 'cool' made SVB a bad bank, and why we need better data and tools with Richard Holden. SVB gathered a lot of deposits during the pandemic technology funding boom, tripling in size. But the bank was not great at finding lending opportunities, so it bought a number of fixed-income securities right when prices were highest. The team estimated that SVB saw a -15.7% decline in asset value.

But it’s all about the liabilities, baby

But looking at just the asset impairment missed the bigger issue. In Jiang’s estimates, SVB’s asset losses were bad, but not the worst. It was higher than average (-15.7% vs an average loss of -10%), placing it at the 89th percentile. In other words, around 10% of banks had worse loss percentages.

“So the FDIC only did the mark-to-market losses calculation on a small portion of the asset side, they didn’t look at the liability side. I think in order to really understand the key issues of the current banking crisis, we need to understand the liability side. So we look at how much of their deposits are uninsured. Those uninsured deposits are actually runnable.”

What made SVB bank prone to collapse was its liability structure — namely its very high percentage of uninsured deposits. Its assets were primarily funded by uninsured deposits. It ranked 99th percentile in its uninsured deposit / asset ratio. What doomed SVB was too many company treasurers sitting on large uninsured accounts worrying they may not get back all money. They rationally ran. It did not help that many customers were in a small elite community active on social media and in Slack channels. To Jiang and the team, this shows that analyzing liability structure, particularly in uninsured deposits, is crucial to controlling risks of bank runs.

Individual banks by both estimated asset impairment (%) and uninsured deposits/assets

What lies ahead for the banking system?

The research offers critical insights into the current state of banking system. The team ran a scenario analysis to give a ballpark estimate of the size of problem. There is a truism that banking is a confidence game, and whether or not a bank is ultimately solvent depends partly on the beliefs and actions of its depositors. A bank may have enough assets to cover its liabilities if everything is held to maturity and if depositors are willing to stay. The same bank may not survive if enough depositors flee.

The team tested scenarios for the US banking sector for varying percentages of uninsured depositors flight, starting with 10%, 20%, 30%, etc. Insolvent was defined as no longer having enough assets to cover insured deposits. Even a 10% flight of uninsured deposits would render 66 banks insolvent. If 50% of uninsured deposits left, 186 banks would be insolvent representing $300 billion of uninsured deposits. This would entail a $10 billion loss to the FDIC insurance fund to cover insured deposits.

“We did a calculation about how much the government needs to spend if they want to cover all of the uninsured deposits, that's definitely beyond the FDIC deposit insurance. If you compare that to the government balance sheet, they cannot provide an explicit guarantee on all of the uninsured deposits, because it's a large amount. In the end, if you ask me what will happen, the government needs to rely on other banks to take over, like what happened to First Citizens Bank and SVB.”

Authorities are in a tight spot. They need to grapple with moral hazard and legislative constraints. The balanced decision they made on March 12th was to use systemic risk powers to fully guarantee all depositors at SVB and Signature Banks, but to do so on a case-by-case basis rather than explicitly guarantee all future deposits. According to Jiang, this makes sense. They calculated how much a guarantee might have to cover and it would require massive fiscal backing. There is little political appetite for that currently. It’s not a 2008-style collapse but likely a slower motion impact on some banks and on the economy.

If not all deposits are “sleepy,” we may have slower motion “bank walks” that economists such as Luigi Zingales worry about.3 There is particular concern that deposit flight can be faster in this age of digital banking. Reported in the WSJ: “Bank deposits have fallen $363 billion to $17.3 trillion since the beginning of March, Fed data show. Assets in money-market funds have risen $304 billion to a record $5.2 trillion, according to Investment Company Institute data.”4 Zingales discussed this with me Luohan DiTalks: SVB reveals regulatory failings in the age of social media bank runs. Based on Jiang et al’s research, the sector is in need of recapitalization, but upward pressure on rates would make it more difficult.

A deposit insurance subsidized David vs. Goliath?

Another big question has been the potential negative impact on small banks, whichdo not have the too-big-to-fail imprimatur of GSIBs. Given banking is about confidence, this may render some small banks unviable. Will the mega-banks swallow up smaller competitors and get bigger from this crisis?

Some pundits and politicians have argued that not backing all deposits effectively favoring the Goliaths over the Davids. Many argue that small banks play important roles in local economies, and some research support this, as highlighted in a recent WSJ article Local Banks Could Leave Gaps That Are Hard to Fill.5

I asked Jiang if we as a society should think about explicitly helping small banks. Jiang offered a more nuanced take to this question, deriving from the team’s research. Her finding is that the current US deposit insurance system is a de-facto subsidy to small banks. Without it, they would not be able to attract lower-cost deposit funding. Relatively, small banks derive more funding from insured deposits. They also maintain lower capital ratios, which they are allowed to under rules. Small banks were always less viable if left to the whims of the market, but now the crisis has pushed the issue to the forefront. If the old equilibrium is no longer as solid, then perhaps society does need to figure out what a new equilibrium is.

Excerpt from Banking Without Deposits (2020):

Capital requirements, FDIC assessment rates, as well as other forms of regulation are frequently stricter for large banks. Perhaps the most surprising result of our paper is that the banks’ deviation in capital structure choices from those of shadow banks are the largest for small banks. Small banks are substantially less capitalized than shadow banks of corresponding size, and rely substantially less on uninsured debt funding. In other words, insured deposits present a substantially larger part of funding for small banks than large banks. Our results suggest that it is the small banks, which benefit most from the insured deposit subsidy.

Regulators and regulations under scrutiny, can data be better used?

Since the publication of the paper, the team has received tremendous interest from regulators. This is encouraging to hear that the team’s research can make a difference in making banking safer. But it does raise questions of what the regulators should have done with data they were always collecting. For example, why did the regulators not have even some very back-of-the-envelope calculations? Both the problems of interest rate risk for assets and uninsured deposits for liabilities was well known. After all, the 2022 Nobel prize in economics was given for the Diamond-Dybvig bank-run model, which showed how uninsured depositors are prone to run.

So does Jiang have views on solutions? Her past research into shadow banks suggests that higher capital is one approach to making the system more stable. Shadow banks, which presumably do not have the same guarantees, maintain an average capital ratio of 25%, more than twice the 11% of regular banks. Interesting, bank capital was something Matvos researched in a 2017 paper on financial fragility, which suggested that >18% capital requirement led to more stability.6 Of course, economics is about trade-offs. Whether or not this is the best cost-benefit solution is an open question. More regulations on transparency in accounting for mark-to-market losses are also part of the public discussion. The authors note this solution, but also caveat that past regulations often suffer from inconsistency, which Seru studied in a past paper.7

One major takeaway I have after Jiang’s research is sometimes we do not have to rely on banks complying, but rather regulators and other actors can do more effective analysis to highlight areas of risk. As Jiang, notes, this crisis was not a case of a lack of relevant data. And she notes there is already some technology and automation, for example in conducting stress tests. Perhaps there could be more crowdsourcing of analysis and ideas from stakeholders such as the academic community.

Luohan fellow Holden suggested that regulators should not rely on static stress tests on pre-set schedules and deploy much more technology. Importantly, technology could help to make such analysis, modeling, and visualization more robust and comprehensive. Perhaps AI technologies, which have been the talk of the town lately, can be deployed to boost the productivity of the banks. They may also allow their regulators, creditors, and customers, to scrutinize and check.

Jiang believe any single rule or technology will never be a panacea. The ultimate solution will be people who continually improve models and identify the areas of underperformance. To that end, research like the paper Jiang discussed with us today does a lot to help make our financial system safer for all participants.

Jiang, Erica Xuewei and Matvos, Gregor and Piskorski, Tomasz and Seru, Amit, Monetary Tightening and U.S. Bank Fragility in 2023: Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs? (March 13, 2023). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4387676

FDIC: Speeches & Testimony - 03/06/2023 - Remarks by FDIC Chairman Martin Gruenberg, Institute of International Bankers, https://www.fdic.gov/news/speeches/2023/spmar0623.html

Koont, N., Santos, T., & Zingales, L. (2023, April 4). Destabilizing Digital “Bank Walks.” ProMarket. https://www.promarket.org/2023/04/04/destabilizing-digital-bank-walks/

Wallerstein, E., & Timiraos, N. (2023, April 5). Deposit Outflows Shine Light on Fed Program That Pays Money-Market Funds. WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/articles/deposit-outflows-shine-light-on-fed-program-that-pays-money-market-funds-6763e11c

Lahart, J., & Demos, T. (2023, March 18). Local Banks Could Leave Gaps That Are Hard to Fill. WSJ. https://www.wsj.com/articles/local-banks-could-leave-gaps-that-are-hard-to-fill-841966a9

Egan, Mark, Ali Hortaçsu, and Gregor Matvos. 2017. "Deposit Competition and Financial Fragility: Evidence from the US Banking Sector." American Economic Review, 107 (1): 169-216.

Sumit Agarwal & David Lucca & Amit Seru & Francesco Trebbi, 2014. "Inconsistent Regulators: Evidence from Banking," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Oxford University Press, vol. 129(2), pages 889-938.